Duck, Duck, are you the Goose?

The AI bubble is frothy, don’t be left holding the bag

My late grandfather was quite the philosopher. No matter the situation, he had a great line for it. Here’s a couple of good ones:

‘A fish stinks from its head = Leadership matters.

‘Every pig hangs by its own two feet’ = you’re responsible for your own actions.

“If it walks like a duck, quacks like a duck… It’s a duck” = It’s usually what it seems.

That last one, is such an appropriate line for what’s happening right now in AI. The present AI economy waddles and quacks. The major players are participating in a really wild game of duck, duck goose.

Keeping with the duck theme, let’s join them and play a quick game with them.

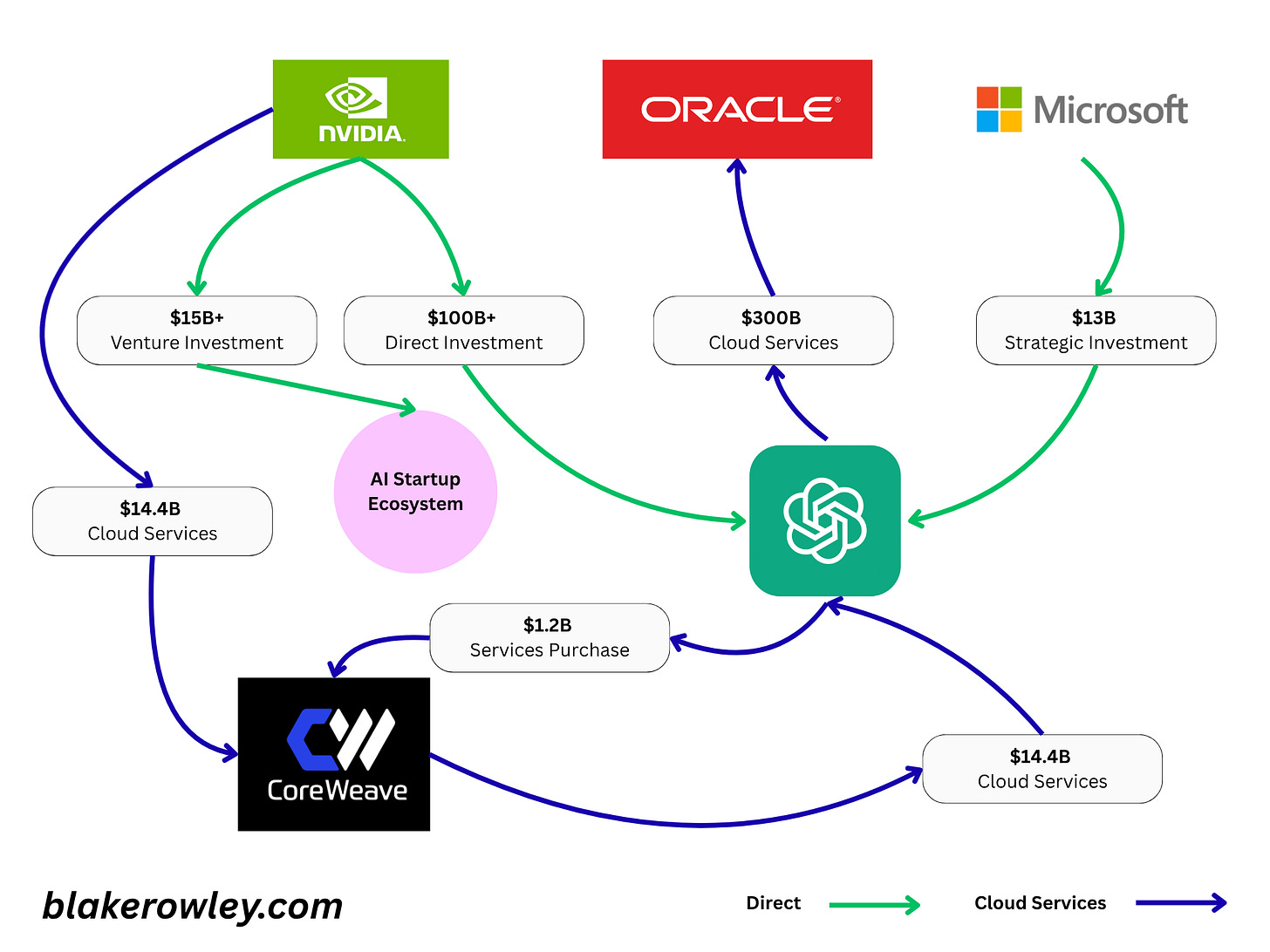

Nvidia is committing up to $100 billion to OpenAI, while also planning to supply it with the very systems that money buys.

Duck.

Oracle signed an eye‑watering $300 billion compute deal with OpenAI and promptly started raising debt to build the DC’s that run, wait for it, Nvidia gear for OpenAI.

Duck.

CoreWeave expanded its OpenAI contracts to $22.4 billion this year and separately inked a $6.3 billion “we’ll buy your unused capacity” backstop with Nvidia that runs through 2032.

Duck.

$450B in circular flows.

$250B revenue shortfall.

Concentration past dot‑com levels.

And, no one has the funds to pay. It’s all coming from ‘future revenue’ opportunities.

I don’t know about you, but that looks suspiciously like everyone funding everyone else written on an IOU.

Duck.

Let’s sum the $450B.

OpenAI to Oracle: $300.0B (Cloud Services)

Nvidia to OpenAI: $100.0B (Direct Investment)

CoreWeave to OpenAI: $14.4B (Cloud Services)

Nvidia to CoreWeave: $6.3B (Cloud Services/backstop)

Microsoft to OpenAI: $13.0B (Strategic)

OpenAI to CoreWeave: $1.2B (Services Purchase)

Yep.

Who’s going to be left holding the bag?

Hopefully not us.

Much like the very catchy Fatboy Slim “eat, sleep, rave, repeat” tune, my awful attempt at a graphic says the quiet part out loud.

Invest. > Earn. (“revenue”) > Purchase. > Report. (“demand”) > Repeat.

Okay. Maybe not as catchy as I thought.

GOOSE!!!!!

P.S I spent WAY TOO LONG making a graph of this, please appreciate it.

Economically, not legally, this is Ponzi‑adjacent.

The loop works beautifully while confidence and credit expand. It works terribly as soon as someone looks at it with their glasses on.

Ahhh it’s so meme-able.

Literally, think of this lovely nanna as you look at the following graph.

Spend: $50B to $400B (2022–2025)

Revenue: $12B to $150B

Gap: $38B to $250B compounding at ~87% a year

Coverage: revenue rises from 24% to 37.5% of spend

In translation, in 2025, each dollar of AI spend is met by $0.38 of revenue.

Would you invest your nanna’s money in that?

I don’t think so.

I’m gonna make it even worse.

History, yo.

Let’s take a look into some really interesting past bubble popping schemes.

The Railroads

AOL Barter Deals

Telecom Equipment Financing.

Long story short if you don’t have time to read.

Each bubble perfected the art of financial engineering while seemingly learning from its predecessors’ mistakes.

In the Railroad Vendor Financing (1845–1847), $2 billion in equipment financing where manufacturers funded customer purchases.

In the AOL Barter Deals (2000–2002), $600 million in cross-advertising and service arrangements.

In the Telecom Equipment Financing (1999–2001), $25 billion in vendor financing by Nortel, Lucent and Cisco.

In every case, it all came undone and someone was Goose.

The AI circular investment web represents an 18x increase over the telecom vendor financing bubble and 750x increase over AOL’s schemes.

The railroads though, still win

Alright.

A bit of storytelling and history blended.

Let’s start with the most insane.

The OG.

Gotta hand it to ol’ Hudson. He really created something here.

I’m no Margot Robbie in a bath (Wolf of Wall Street), so hopefully my data backed insights and storytelling make up for it.

The railroads

George Hudson

The story begins with George Hudson who inherited £30,000 in 1827 and transformed it into control over 1,016 miles of British railway.

Hudson was the OG duck, duck goose player.

He pioneered what would become the template for all subsequent circular financing schemes, using initial success to create the illusion of demand that justified ever-larger investments.

George Hudson controlled 1,016 miles of railway by 1846 through £25 million in circular financing and extensive parliamentary bribery.

Duck money.

Hudson’s method was elegantly simple yet devastatingly effective. He would form a new railway company, personally guarantee dividends of 6%, then use the initial capital to purchase equipment from the same suppliers who had invested in his companies.

By 1845, Hudson controlled 15 separate railway companies through a web of cross-investments, circular financing arrangements and strategic parliamentary corruption totalling £25,000 in bribes.

What unravelled everything?

The equipment vendor financing web.

The goose.

The railway bubble’s circular financing centred on equipment manufacturers like locomotive builders and rail producers. Hudson would arrange for these suppliers to provide “deferred payment terms”, essentially lending money to railway companies to purchase their own products.

By 1847, equipment vendor financing had reached £15 million annually, representing nearly 35% of total railway investment.

The genius of Hudson’s scheme was its self-reinforcing nature.

Successful railways attracted investors, investor capital funded equipment purchases, equipment sales generated profits for suppliers and supplier profits were reinvested in new railway ventures.

The same £1 might circulate through this system five times, each time appearing as “new investment” in the rapidly inflating railway sector.

All I gotta say is… Duck.

Hudson’s empire unraveled when parliamentary committees discovered his accounting manipulations in 1849.

Duck.

He had been paying dividends from share capital rather than profits, selling land he didn’t own to his own companies and inflating construction costs to justify higher share prices.

Goose.

The revelations triggered a 67% collapse in railway share prices and left thousands of investors with worthless paper.

In total, across the whole industry, railway capital investment reached £44 million in 1847, representing an extraordinary 7% of British GDP.

In today’s money, this cumulative investment of approximately £225 million (1843–1850) equates to roughly $4 trillion, making it proportionally larger than any subsequent infrastructure bubble.

Railway stock prices peaked at 2,062 index points in August 1845, then collapsed 67% to 673 by 1850.

Ouch.

Seeing any parallels?

Tell me this doesn’t line up with four hyper-scalers announcing identicalmega‑campuses within the same grid constraint and despite limited evidence of sufficient demand to support such capacity.

What’s so interesting about this, is that the physical infrastructure remained.

The railways Hudson built became the backbone of British industrialisation for the next century, proving that circular financing bubbles often create genuine long-term value even as they destroy investor wealth.

Yes, AI is a bubble.

Yes, it is transformative.

Yes, we still use railways.

Yes, we will use these DC’s.

They can all be true at the same time.

Maybe it will all be owned by Evil Mega Corp, or our AI overlords, not Google and Microsoft.

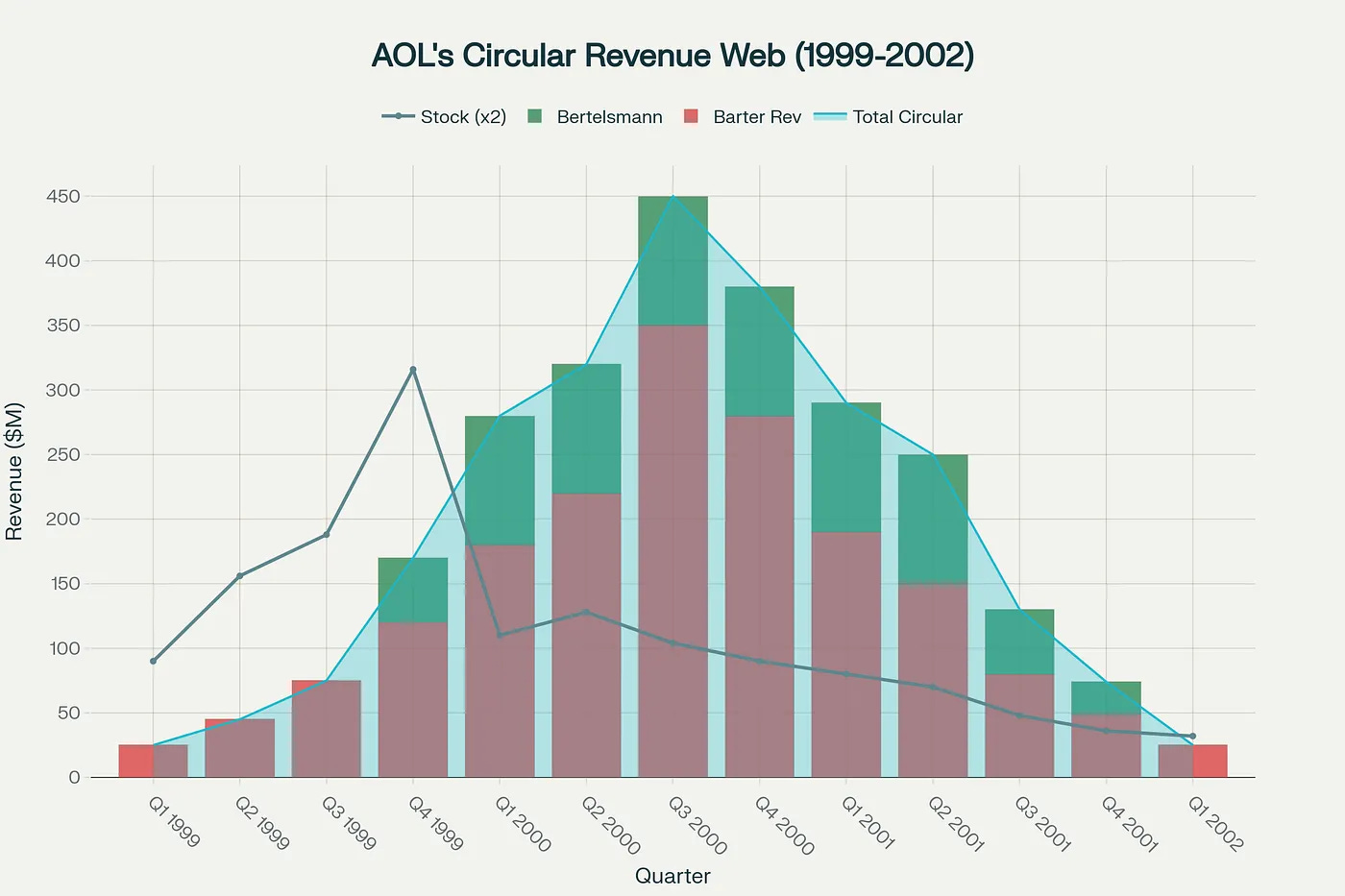

AOL’s barter deal revolution

America Online (AOL) perfected circular revenue arrangements in ways that would make daddy Hudson jelly.

Unlike the railway magnate’s crude equipment financing, AOL created sophisticated “barter deals” where advertising services were exchanged for equity stakes, cross-promotional agreements and reciprocal purchasing arrangements.

AOL’s circular revenue schemes peaked at $450 million in Q3 2000 during the Time Warner merger, supporting a stock price of $158

AOL’s circular revenue machine operated on three levels.

Basic barter deals where AOL exchanged online advertising for services or equity in dot-com startups.

The massive Bertelsmann arrangement worth $400 million, where AOL’s European joint venture partner purchased AOL advertising services as part of a complex media partnership.

Cross-promotional deals where AOL would invest in or partner with companies that then spent money on AOL services.

Buy. Invest. Buy.

The crown jewel of AOL’s circular revenue scheme was its relationship with German media giant Bertelsmann.

In March 2000, AOL and Bertelsmann signed a joint promotion agreement that ‘appeared’ to be worth $400 million in advertising revenue to AOL over four years.

The reality was more complex.

Bertelsmann agreed to “spend” $400 million on AOL advertising in exchange for preferred placement, cross-promotional services and strategic partnerships that effectively meant AOL was selling advertising to itself.

The SEC later determined that much of this $400 million should have been accounted for as a reduction in the acquisition price of AOL Europe rather than legitimate advertising revenue.

This distinction meant the difference between AOL showing explosive advertising growth versus acknowledging that it was paying for its own revenue.

Not very free market of you, fellas!

Where did it all come undone?

AOL’s circular revenue schemes reached their zenith during the 2000 Time Warner merger negotiations.

Total circular revenue hit $450 million in Q3 2000, representing approximately 9% of AOL’s total advertising income.

Duck.

These arrangements allowed AOL to demonstrate the “hockey stick” revenue growth that justified its $164 billion valuation and convinced Time Warner executives to accept AOL’s inflated stock as merger currency.

Goose.

When the schemes unraveled in 2002–2003, AOL Time Warner took a record $99 billion write down, acknowledged $600 million in questionable revenue and paid $300 million in SEC fines.

The lesson was clear.

Circular revenue arrangements could sustain impossible valuations for years, but the eventual reckoning was proportionally devastating.

I love the quote:

“The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent”.

Do I need to show you my masterpiece graph again?

History repeats itself.

Just not in the timeframe we think.

The telecom equipment frenzy

The telecom equipment bubble took circular financing to unprecedented industrial scale. Companies like Nortel, Lucent and Cisco discovered that in a rapidly expanding market, vendor financing wasn’t just a competitive tool, it was the primary driver of growth.

Telecom vendor financing reached $33 billion at peak in 2000, with Lucent leading at $10.5 billion before collapsing in 2001.

The vendor financing explosion began modestly in 1999 with $3.5 billion in total industry lending, but within 18 months had grown to $32.8 billion by Q4 2000. Lucent alone had $7.2 billion in customer financing outstanding by March 2000, a 65% increase from the previous year.

Nortel’s vendor financing represented nearly 7% of its total revenue, while Cisco extended $2.4 billion in customer loans despite having minimal disclosure requirements.

Cue the phantom demand creation machine.

The telecom vendor financing web created artificial demand through multiple circular mechanisms. Equipment manufacturers lent money to startup telecom carriers, who used the funds to purchase equipment from those same manufacturers. The manufacturers then reported this as organic revenue growth, which supported stock prices and enabled them to raise more capital to fund additional vendor financing.

More circles.

Lucent’s deal with Fidelity Holdings exemplifies the absurdity.

Get this.

Another Daddy Hudson banger.

A small car dealership with a tiny Internet division received $400 million in vendor financing to purchase Lucent equipment, despite having only $1.3 million in annual sales.

The arrangement was possible because Lucent took equity stakes and guaranteed residual values, meaning it was essentially buying its own products through intermediaries.

So Blake, where did this goose come from?

Well, this one was rough.

The telecom vendor financing collapse was swift and merciless.

By Q1 2001, total industry vendor financing had fallen to $25.5 billion and by Q2 2001 it was down to $18.2 billion as companies defaulted on obligations and equipment values plummeted. Lucent took a $501 million charge in fiscal 2000 for unpaid customer debts, equivalent to 41% of its annual earnings.

The human cost was staggering.

WorldCom collapsed with $100 billion in debt, Global Crossing failed with $25 billion in obligations and 23 major telecom companies went bankrupt in the US alone.

The equipment manufacturers that had enabled this expansion through vendor financing saw their stock prices fall 80–90%, destroying trillions in market capitalisation.

So what have we, a society, learnt from history?

Spoiler, nothing.

We are creatures of habit.

The AI Circular Investment Explosion

It’s like we never learn.

$615 Billion and Growing.

An infinite money glitch.

No Gooses? (There’s always a Goose).

The NVIDIA-OpenAI-Oracle triangle represents the most sophisticated circular financing arrangement in economic history, with over $615 billion in interconnected deals that create the appearance of massive demand while the same money circulates through an increasingly complex ecosystem.

AI circular investment has exploded to over $615 billion by Q2 2025, dwarfing all previous bubble financing schemes.

Unlike previous bubbles, this arrangement involves the world’s most valuable companies. NVIDIA ($3.4 trillion market cap), Microsoft, Meta and others whose combined market capitalisation exceeds $15 trillion.

The systemic risk is unprecedented.

When 25% of the S&P 500’s value depends on AI revenue growth and that growth is sustained by circular financing arrangements, the potential for cascading failure exceeds anything seen in previous technology bubbles.

The math only works if artificial general intelligence (AGI) arrives on schedule and generates the revenue necessary to justify current investment levels.

Goose, you up?

History suggests that while circular financing bubbles destroy investor wealth, they often create valuable infrastructure that benefits society long-term.

British railways, internet backbone, fibre optic networks and potentially AI data centres all represent genuine technological advances funded by speculative excess.

The cruel irony is that the most visionary investors, those who correctly identify transformative technologies often suffer the greatest losses during the speculative phase.

The ultimate beneficiaries are companies that can “free ride” on the infrastructure built during the bubble, acquiring capacity at pennies on the dollar after the collapse.

We can all agree, it’s a duck and the goose is coming.

Don’t be left holding the bag short term.

We’ll all benefit from this long term.

For my Gen Z readers, translation.

YOLO. But don’t HODL.

Until next time,

Blake